Research Article - Neuropsychiatry (2017) Volume 7, Issue 6

Wrist-Ankle Acupuncture for Precompetition Nervous Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial

- Corresponding Author:

- SWei Gu

Changhai Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine

Second Military Medical University

168 Changhai Road, Yangpu District, Shanghai 200433, China

Tel: +86 13761312876

Shuang Zhou

Changhai Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine

Second Military Medical University

168 Changhai Road, Yangpu District, Shanghai 200433, China

Tel: +86 13761312876

Abstract

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate the effects of wrist–ankle acupuncture (WAA) for precompetition nervous syndrome and provide data for further research.

Methods: The study was designed as a randomized controlled, single-blind trial on the sprinting distance items during the annual track and field events (2013–2015) of a university in Shanghai, China. A total of 103 enrolled participants (age 18–40 years, both males and females) were randomly assigned to receive WAA therapy (n = 52) or sham acupuncture (n = 51). The group allocations and interventions were concealed to participants and statisticians. The competition state anxiety scale was used as the primary outcome measure. Expectation and treatment credibility scale (ETCS) and participants’ feeling of acupuncture questionnaire were applied as secondary outcome measures.

Results: A significant difference was observed in somatic state anxiety and cognitive state anxiety in the WAA group from pre- to post treatment. No significant change in the score of selfconfidence state was found in both the groups. Cognitive state anxiety improved significantly in the post treatment WAA group compared with the sham group. Moreover, the result of ETCS showed participants in the WAA group had more expectation and treatment credibility. The visual analogue scale scores indicated no significant difference between groups for the participants’ feeling of acupuncture.

Conclusions: WAA therapy could efficiently alleviate anxiety state, especially in terms of the improvements in the somatic and cognitive status, under certain circumstances.

Keywords

Wrist-ankle acupuncture (WAA), Precompetition nervous syndrome, Anxiety, Randomized controlled trial

Introduction

The gaps in athlete physical and technical levels in modern competitive sports are becoming smaller, while the psychological factor gradually becomes an important part. To a large extent, the result of the competition is directly influenced by athletes’ psychological quality. Precompetition nervous syndrome is a common psychological problem manifested by the excessive anxious response to the environment of high pressure before sport competition. These uncontrolled emotions and negative cognitions have adverse effects on the performance [1-3]. Various techniques, including meditation, self-breathing training, visuomotor behavior rehearsal, biofeedback training, even hypnosis, and cognitive behavioral therapies, were commonly applied to control athletes’ emotions [4]. However, the clinical trial evidence supporting the lasting effectiveness of these methods for athletes is limited. The robust intervention to consistently control performance anxiety is also critically needed.

In the 2010 Asian Games of Guangzhou, a South Korean player competed with her rival on the game of Go with acupuncture to keep herself relaxed and calm. Alternative medicine therapies such as acupuncture can be a promising and feasible option for players’ mental preparation, which gives a lot of enlightenment. Acupuncture has been widely used in treating various types of disorders of spirit and emotion, such as insomnia, depression, and anxiety [4-10]. However, traditional acupuncture treatments emphasize “needling sensation,” which gives an unpleasant feeling to some players. Knowledge of these effects has impeded the wider acceptance of traditional acupuncture treatments in the games. Wrist–ankle acupuncture (WAA) is a modern acupuncture technique invented and developed by Professor Zhang Xinshu and his colleagues from Changhai Hospital of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China, in the 1970s [11]. The theory of WAA has a unique system of its own, which is quite different from that of the traditional acupuncture [12]. WAA does not produce the “needling sensation” and has demonstrated good effects on mental and nervous disorders. More importantly, no pain and “needling sensation” during the performance of WAA imposes minimal psychological stress to the player and hence is easily accepted.

Previous studies confirmed the efficacy of WAA for pre-examination anxiety [13]. In this study, it was observed that WAA could significantly alleviate the examination tension, and the treatment had high security. To date, no studies have investigated the application of WAA for managing precompetition anxiety in athletes. The present study aimed to investigate the effects of WAA for athletes with precompetition anxiety in annual track and field events.

Methods

The protocol of this study was published in detail during the trial [14].

▪ Study design

The study was designed as a randomized controlled, single-blind trial to evaluate the effects of WAA on precompetition anxiety. The trial was conducted in annual track and field events of Second Military Medical University.

▪ Key inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

(1) University students, aged 18-40 years, including both male and female participants

(2) The wrist ankle acupuncture treatment not yet received by the patient;

(3) The informed consent form signed by the patient

Exclusion criteria

(1) Participants with precompetition nervous syndrome participants using drugs or other systems at the same time

(2) Participants with a history of mental illness or physical disease

(3) Patients with depression trend (selfrating depression scale, SDS ≧41).

▪ Data collection

All the participants were asked to complete two identical versions of a questionnaire including competition state anxiety scale (CSAI)-2 and expectation and treatment credibility scale (ETCS) before and after the treatment. The first questionnaire needed to be completed 30 min before the treatment, while the second one was collected 30 min after the treatment. Meanwhile, participants’ feeling of acupuncture and adverse effect questionnaire was prepared for the subjects 30 min after the treatment.

▪ Treatment regimen

Participants were required to receive one treatment 3 h before the track event sessions (to minimize uncertainty in the selection of different events, only the sprinting distance players were the subjects).

▪ Interventions

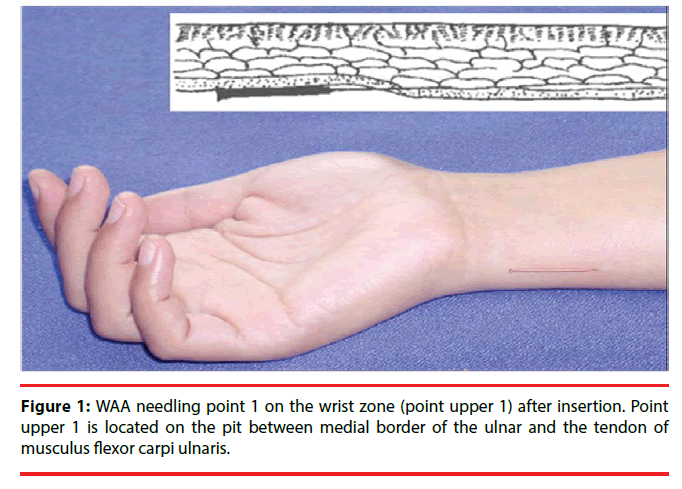

The treatment scheme originates from the principles of WAA and has been practiced in previous clinical trials for several decades [11-17]. According to the theory of WAA, each side of the body and each limb are longitudinally divided into six zones, and one needling point is defined in each zone at the wrist or ankle. Needling point 1 on the wrist zone (point upper 1) can relieve the disorder of emotion. For participants in the present study, precompetition anxiety belonged to the disorder of emotion; therefore, all subjects were needled at point 1 at both wrists (Figure 1).

WAA group: WAA was performed on point upper 1 at both wrists 3 h before the track event sessions. The needle was retained for 30 min. The subjects were asked to stay in a sitting position, wearing an eye mask. The target point was disinfected with an iodophor disinfectant (Shanghai Likang Disinfectant Hi-tech Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). The processed needles were also held with three right-hand fingers (thumb, index finger, and middle finger). The skin near the target point was gently pressed with the left thumb to make it slightly taut. A disposable sterile WAA needle (filiform needle with 0.25 mm in diameter and 25 mm in length, Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory, Jiangsu Province, China) was held with three right-hand fingers (thumb, index finger, and middle finger). Then, the needle tip was swiftly inserted into the skin at the target point at an angle of 30°. The needle was lowered to the horizontal position and slowly advanced until the entire needle (except the handle) entered the subcutaneous tissue. The handle was then fixed to the skin with an adhesive tape. The needles were retained in the subcutaneous tissue for 30 min. For a successful WAA treatment, the patient felt only a negligible stabbing pain when the tip of the needle pierced the skin. No other needling sensation was found. A single registered acupuncturist, with at least 1 year of previous WAA experience, administered the care to all subjects [11,15].

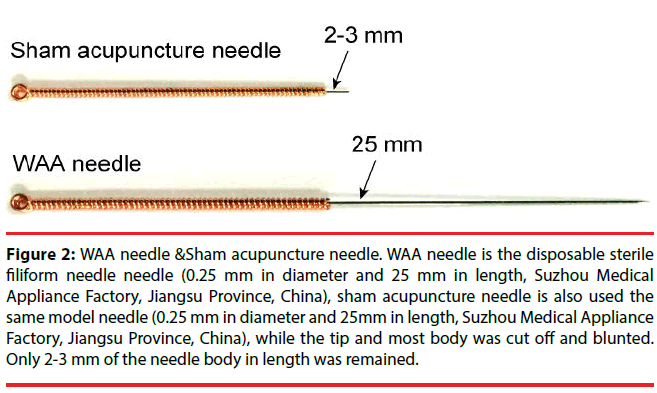

Sham acupuncture group: Sham acupuncture was performed on point 1 at the wrists 3 h before the track event sessions. The needle was retained for 30 min. The subjects were asked to stay in a sitting position, wearing an eye mask. The target site was also disinfected with an iodophor disinfectant (Shanghai Likang Disinfectant Hitech Co. Ltd.). The tip and most body of the disposable sterile acupuncture needle (filiform needle with 0.25 mm in diameter and 25 mm in length, Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory, Jiangsu Province, China) (Figure 2) were cut off and blunted. Only 2–3 mm of the needle body in length remained. The processed needles were also held with three right-hand fingers (thumb, index finger, and middle finger). The skin near the target site was gently pressed with the left thumb to make it slightly taut. The needle tip swiftly punctured the skin at the target point at an angle of 30° (the tip actually did not pierce the skin). Then, the needles remained on the skin of the point horizontally for 30 min. The handle was also fixed to the skin with an adhesive tape. For a successful sham treatment, the patient felt only a negligible stabbing pain when the tip of the needle pierced the skin. No other needling sensation was found. A single registered acupuncturist, with at least 1 year of previous WAA experience, administered the care to all subjects.

Figure 2: WAA needle &Sham acupuncture needle. WAA needle is the disposable sterile filiform needle needle (0.25 mm in diameter and 25 mm in length, Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory, Jiangsu Province, China), sham acupuncture needle is also used the same model needle (0.25 mm in diameter and 25mm in length, Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory, Jiangsu Province, China), while the tip and most body was cut off and blunted. Only 2-3 mm of the needle body in length was remained.

▪ Randomization and blinding

Randomization and blinding methods were applied according to the protocol in the study. An outside researcher who was not allowed to directly contact with the participants performed computerized randomization. The assessor was also blinded to the treatment allocation. The acupuncturist performing the WAA intervention and sham WAA intervention could not be completely blinded, but he was not allowed to reveal any information about treatment procedures and outcomes to the participants or the assessor. Thus, both the participants and the assessor could not distinguish clearly which intervention was given. A sealed envelope containing the allocation sequence number for each participant was opened after each participant met eligibility criteria and informed consent was obtained.

▪ Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

The detailed sample size calculation has been described in the protocol published in trials. The result was a total required sample size of 86(43 in each group). With a maximum dropout tolerance of 15%, 7 participants were needed for each group. Therefore, 100 participants were needed for the trial (50 in each group). The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS15.0 statistics software (SPSS, IL, USA), and the statistician was blinded from the allocation of groups. For the between-group comparisons at baseline, either the chi-square test or independent two-sample t test was used. For quantitative data, the distribution pattern and homogeneity of variance were examined. In the case of a symmetric distribution, the mean (M) ± standard deviation would be used for statistical description. The paired-samples t test was examined to compare the differences between the quantitative indexes before and after the treatment in one group, whereas the independent-samples t test was used for comparison between groups. The entire statistical test used a bilateral examination, and a P value < 0.05 meant statistically significant differences.

▪ Primary outcome

Competition state anxiety scale-2: The CSAI- 2 questionnaire was compiled by Martens et al. based on the theory of multidimensional competition state anxiety [18]. The revision of CSAI-2 was re-corrected by ZhuBeili [19]. The scale was composed of three subscales, each subscale having nine items. Scores were from 9 to 36. A higher score meant higher cognitive state anxiety, somatic state anxiety, and state self-confidence. It was the primary outcome to assess the competitive anxiety and efficacy of treatment.

▪ Secondary outcomes

Expectation and Treatment Credibility Scale: ETCS included four questions to test the credibility from different angles. Participants needed to grade themselves with the extent of 0–10 points according to their immediate feelings (0 meant totally did not; 10 means absolutely did) [20].

ETCS1: I am sure that the treatment will reduce the symptom of anxiety during the events.

ETCS2: I think the therapy is reasonable for the psychological intervention during the events.

ETCS3: I will recommend this therapy for my friends.

ETCS4: I believe that this therapy can also treat other diseases.

Participants’ feeling of acupuncture and adverse effect questionnaire

Participants’ feeling of acupuncture questionnaire was used to determine the success of sham acupuncture implementation. A difference in acupuncture feeling between two groups’ participants was an important index to evaluate the sham acupuncture effect.

The questionnaire included three aspects: the feeling of the needle touching the skin; the feeling of the needle penetrating the skin; and acupuncture pain intensity evaluated using the visual analogue scale (VAS) with the extent of 0–10 points. Adverse events included bleeding, fainting, and so forth.

Results

▪ Patient enrolment

The study was carried out from June 2013 to June 2015 annual track and field events in Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China. The flow of participants through the trial is shown in Figure 3. Of the 115 potential screened participants, 9 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 106 participants were included; 53 participants were allocated to the WAA group, but one dropped out during the treatment period. Another 53 participants were allocated to the control group, but two dropped out without completing the questionnaire; 97.16% of both group participants finished the study period.

▪ Analysis of baseline data

The baseline characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1. No difference was observed between the two groups in terms of sex, age, and SDS scores (P = 0.862, 0.475, and 0.764).

| WAA (n = 52) | Sham (n = 51) | P b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 39 a | 39 a | 0.862 |

| Female | 13 a | 12 a | |

| Age (M ± SD, year) | 21.46 ± 1.65 | 21.22 ± 1.83 | 0.475 |

| SDS scores | 30.52 ± 4.34 | 30.76 ± 3.92 | 0.764 |

a “Gender” value in numbers; other values are mean ± SD.

b/P value of comparison between groups.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of participants.

▪ Competition state anxiety scale

Table 2 shows a significant relieving effect of WAA on somatic state anxiety and cognitive state anxiety. The competitive state anxiety in the sham group did not sufficiently improve in the post treatment period compared with the pretreatment period.

| WAA (n = 52) | Sham (n = 51) | Pc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indexa | Pb | Indexa | Pb | |||

| Somatic State Anxiety Score (mean ± SD) | Before treatment | 18.25 ± 5.78 | < 0.001 | 16.67 ± 6.03 | 0.419 | 0.177 |

| After treatment | 16.69 ± 5.86 | 16.20 ± 6.07 | 0.674 | |||

| Cognitive State Anxiety Score (mean ± SD) | Before treatment | 16.54 ± 5.00 | 0.001 | 15.41 ± 4.77 | 0.340 | 0.245 |

| After treatment | 14.17 ± 4.36 | 16.16 ± 5.17 | 0.038 | |||

| State Self-confidence Score (mean ± SD) | Before treatment | 22.17 ± 5.90 | 0.856 | 23.43 ± 6.58 | 0.313 | 0.309 |

| After treatment | 22.31 ± 6.46 | 24.22 ± 7.49 | 0.169 | |||

SD, standard deviation.

aValues are mean ± SD.

bP value of comparison within the group.

cP value of comparison between groups.

Table 2: Comparison of CSAI-2 scores before and after the treatment in two groups.

Somatic State Anxiety Score: A remarkable change in the somatic state anxiety score was found from pre- to post treatment (P < 0.001) in the WAA group, but the difference was negligible in the sham group (P = 0.419). The differences between the WAA and sham groups both before and after the treatment were not statistically significant (P = 0.177 and 0.674, respectively).

Cognitive State Anxiety Score: A significant improvement (P = 0.001) was observed in the WAA group from pre- to post treatment. However, the improvement was not significant in the sham group (P = 0.340). No statistical difference was found between the WAA and sham groups before the treatment (P = 0.245), but the improvement was significant after the treatment (P = 0.038).

Self-confidence State Score: No significant change occurred from pre- to post treatment in both the WAA and sham groups (P = 0.856 and 0.313, respectively). The differences were also insignificant between groups before and after the treatment (P = 0.309 and 0.169, respectively).

▪ Expectation and Treatment Credibility Scale

Table 3 shows significant changes in the scores on ETCS1, ETCS2, ETCS3, and ETCS4 in the WAA group (P < 0.001, P = 0.003, P = 0.002, and P < 0.001, respectively). The changes were significant on ETCS1 and ETCS4 in the sham group (P = 0.001 and P = 0.023, respectively). The significant differences between groups were found only in ETCS1, ETCS2, and ETCS3 scores after the treatment (P = 0.002, P = 0.027, and P = 0.046, respectively).

| WAA (n = 52) | Sham (n = 51) | Pc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indexa | Pb | Indexa | Pb | ||||

| ETCS1 | Before treatment | 4.52 ± 1.83 | < 0.001 | 4.59 ± 2.20 | 0.001 | 0.863 | |

| After treatment | 6.58 ± 1.86 | 5.29 ± 2.20 | 0.002 | ||||

| ETCS2 | Before treatment | 5.27 ± 2.32 | 0.003 | 4.90 ± 1.66 | 0.296 | 0.357 | |

| After treatment | 6.13 ± 1.94 | 5.18 ± 2.36 | 0.027 | ||||

| ETCS3 | Before treatment | 4.65 ± 2.33 | 0.002 | 4.49 ± 2.22 | 0.176 | 0.716 | |

| After treatment | 5.75 ± 1.95 | 4.86 ± 2.48 | 0.046 | ||||

| ETCS4 | Before treatment | 4.50 ± 2.38 | < 0.001 | 4.43 ± 2.52 | 0.023 | 0.887 | |

| After treatment | 5.63 ± 2.43 | 4.88 ± 2.73 | 0.142 | ||||

SD, Standard deviation.

aValues are mean ± SD.

bP value of comparison within group.

cP value of comparison between groups.

Table 3: Comparison of ETCS scores before and after the treatment in two groups.

▪ Participants’ feeling of acupuncture and adverse events

Further, 49 participants had the feeling of the needle touching the skin, and 46 had the feeling of the needle penetrating the skin in the WAA group (n = 52), compared with 46 and 47 participants in the sham group (n = 51), respectively. However, the VAS scores indicated no significant difference between groups (P = 0.850). No adverse event was reported in the two groups during all the treatments (Table 4).

| Groups | n | Feeling of needle touching the skin | Feeling of needle penetrating the skin | VAS score | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WAA | 52 | 49 | 46 | 1.66 ± 1.40 | 0 |

| SHAM | 51 | 50 | 47 | 1.89 ± 1.52 | 0 |

| P= 0.850 |

Table 4: Participants’ feeling of acupuncture and adverse events.

Discussion

In modern competitive sports, the psychological factor has been implicated in determining the result of the competition. The aim of this study was to examine the effects of WAA on precompetition nervous syndrome. According to WAA’s unique theoretical system, it has many advantages in reliving various types of anxiety. It does not require any needling sensation, such as sourness, numbness, distention, and pain. Also, it is more acceptable for athletes than common filiform needle intervention. Therefore, a randomized controlled, singleblind trial could be innovatively designed with a nonpenetrating sham wrist–ankle acupuncture group, which was able to provide high-quality evidence for WAA treating precompetition anxiety [21,22].

CSAI-2, composed of three subscales indicating the cognitive state anxiety, the somatic state anxiety, and the self-confidence state, was chosen to assess competitive anxiety and efficacy of treatment as the primary outcome. The results of the study showed that WAA therapy could efficiently alleviate the athletes’ anxiety state, especially in terms of somatic and cognitive aspects, as the differences in scores between pre- to post treatment within these two groups were significant. However, sham therapy did not show a similar effect on anxiety relief. The improvement in cognitive state anxiety after WAA treatment was also remarkable compared with the sham group. No statistical difference was observed in the self-confidence state between pre- and post-treatment or between two groups, indicating that WAA had negligible improvement on athletes’ self-confidence. This result was reasonable and related to the inclusion criteria of participants without WAA experience because the participants had no confidence in the interventions. Otherwise, it showed that WAA therapy could efficiently alleviate the athletes’ somatic and cognitive status without subjective cognitive interference.

Comparison of ETCS scores showed significant improvements in ETCS1, ETCS2, ETCS3, and ETCS4 from pre- to posttreatment in the WAA group, whereas the sham group had statistical difference only in ETCS1 and ETCS4. Participants in the WAA group had more expectation during the treatment experience, although they had no cognition on WAA’s treatment credibility. It could be taken as indirect evidence confirming the immediate alleviating effect of WAA.

The results showed that the sham acupuncture also influenced CSAI-2 and ETCS scores during the treatment. The participants’ feeling of acupuncture questionnaire was designed to determine the success of sham acupuncture implementation so as to eliminate psychological factors. The VAS scores indicated no significant difference between groups and suggested that participants had difficulties in distinguishing a certain intervention in the treatment. Therefore, it is believed that the present trial was successful on effective placebo intervention and could provide high-quality evidence for the efficacy of WAA in precompetition nervous syndrome. Meanwhile, no side effect was observed in all the included participants, indicating that WAA therapy did not produce the “needling sensation” and hence was easily accepted.

The present study also had a limitation. Higher levels of competition can cause more precompetition anxiety and provide more credible evidence. The trial reflected only the treatment effects under certain circumstances because it was not conducted during large national sporting events.

Conclusions

The present study showed that WAA therapy could efficiently alleviate anxiety state, especially in terms of the improvements in the somatic and cognitive status under certain circumstances. The result might be useful for the athletes in a national athletic meet or Olympic Games in the future.

Author affiliations

Changhai Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, Shanghai, China

Contributors

SS designed the protocol and drafted the article. YY analyzed the data. YYL completed the randomized grouping. QXL was in charge of recruitment and treatment of participants. ZS was the project director. GW critically reviewed the entire manuscript and provided significant feedback. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Tengfei program of Shanghai Sports Bureau, China (No.11TF021) and Shanghai three years’ development of Chinese medicine plan (ZY3-CCCX-3-7002).

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Ethics review and informed consent

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Chinese Ethics Committee of Registering Clinical Trials (ChiECRCT-2013024). All participants are required to provide informed consent.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- Naylor S, Burton D, Crocker PRE. Competitive anxiety and sports performance. In J. M. Silva, & D. E. Stevens (Eds.), Psychological foundations of sport 3(1), 132-154 (2002).

- Gill DL, Williams L. Psychological dynamics of sport. Champaign: Human Kinetics (2008).

- Hausenblas HA, Saha D, Dubyak PJ, et al. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Integr. Med 11(6), 377-383 (2013).

- Pesce M, Fratta IL, Ialenti V, et al. Emotions, immunity and sport: Winner and loser athlete's profile of fighting sport. Brain. Behav. Immun 46(1), 261-269(2015).

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc 18(1), 23-33 (2009).

- YouGov. Plc. Mental Health Awareness Week Survey, April (2014).

- Chan YY, Lo WY, Yang SN, et al. The benefit of combined acupuncture and antidepressant medication for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord 176(1), 106-117(2015).

- Errington-Evans N. Randomised controlled trial on the use of acupuncture in adults with chronic, non-responding anxiety symptoms. Acupunct. Med 33(2), 98-102 (2015).

- Cao H, Pan X, Li H, et al. Acupuncture for treatment of insomnia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Altern. Complement. Med 15(11), 1171-1186 (2009).

- Huo ZJ, Guo J, Li D. Effects of acupuncture with meridian acupoints and three Anmian acupoints on insomnia and related depression and anxiety state. Chin. J. Integr. Med 19(3), 187-191 (2013).

- Zhang XS, Ling CQ, Zhou QH. Practical Wrist-Ankle Acupuncture Therapy. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (2002).

- Lao HH. Wrist-Ankle Acupuncture: Methods and Applications, 2nd ed. New York: Oriental Healthcare Center 1-43(1999).

- Shu S, Li TM, Fang FF, et al. Relieving pre-exam anxiety syndrome with wrist-ankle acupuncture: a randomized controlled trial. J. Chin. Integr. Med 9(6), 605-610 (2011).

- Shu S, Zhan M, You YL, et al. Wrist-Ankle Acupuncture (WAA) for precompetition nervous syndrome: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 16(1), 396(2015).

- Zeng K, Dong HJ, Chen HY, et al. Wrist-Ankle Acupuncture for pain after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in participants with liver cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Chin. Med 42(2), 289-302 (2014).

- Chu Z, Bai D. Clinical observation of therapeutic effects of wrist-ankle acupuncture in 88 cases of sciatica. J. Tradit. Chin. Med 17(4), 280–281 (1997).

- Zhu Z, Wang X. Clinical observation on the therapeutic effects of wrist-ankle acupuncture in treatment of pain of various origins. J. Tradit. Chin. Med 18(3), 192-194 (1998).

- Martens R, Burton D, Vealey RS, et al. Development and validation of the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2. In: Martens R, Vealey RS, Burton D, editors. Competitive Anxiety in Sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics 117–190 (1990).

- Zhu BL. The revision of sports competition state anxiety inventory (CSAI-2 Questionnaire): Chinese Norm. Psychol. Science 17(), 358–362 (1993).

- Lao L, Bergman S, Hamilton GR, et al. Evaluation of acupuncture for pain control after oral surgery: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck. Surg 125(5), 567-572 (1999).

- Tan JY, Suen KPL, Wang T, et al. Sham acupressure controls used in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review and critique. Plos. one 10(7), e0132989 (2015).

- To M, Alexander C. The effects of Park sham needles: a pilot study. J. Integr. Med 13(1), 20–24 (2015).