Case Report - (2018) Volume 8, Issue 4

Recurrent Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesia Associated with Depression in a Bipolar Patient with Comorbid Basal Ganglia Calcification

- Corresponding Author:

- Makoto Ishitobi

Tokyo Aiseikai Takatsuki Hospital Address

Takatsuki Hospital, 178, Miyashita-Cho

Hachiouji city, Tokyo 192-0005, Japan

Tel: +81-042-691-1131

Fax: +81-042-691-1717

Abstract

Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD) is characterized by recurrent and brief attacks of involuntary movement in the trunk and limbs triggered by the sudden initiation of voluntary movement. This report describes a 66-year-old female patient with bipolar disorder (BD) and idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (BGC) who had developed recurrent PKD, which resolved completely with remission of depressive state. Clinicians should regard mood disturbance as a rare, but possible causal factor of transient PKD in subjects with BD and BGC.

Keywords

Bipolar disorder, Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia, Basal ganglia calcification

Introduction

Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD) is characterized by recurrent and brief attacks of involuntary movement in trunk and limbs triggered by the sudden initiation of voluntary movement [1]. In addition to familial and idiopathic cases, symptomatic cases associated with basal ganglia calcification (BGC), also exist [2-4]. BGC is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous condition that is characterized by movement disorders and various neuropsychiatric disturbances including several cases of bipolar disorder (BD) [5,6]. This report describes a 66-year-old female patient with bipolar disorder and idiopathic BGC who developed recurrent PKD, which resolved completely with remission of depressive state. We discuss the clinical significance of BGC in the treatment of BD.

Case Report

A 66-year-old female with bipolar disorder was admitted to our psychiatric inpatient unit complaining of severe depressive mood and her two-month history of paroxysmal episodic involuntary movements. She was described by her relatives as active and cyclothymic temperament by nature. Overall, she had been maintaining good level of functioning until when she was 65 years old. About a year before admission to our hospital, she was compulsorily admitted to inpatient psychiatric unit of other hospital because of severe depressive episode characterized by agitation, suicidal ideation and paroxysmal involuntary movements. Medications including duloxetine, sertraline and quetiapine were unsuccessfully tried. Finally, mirtazapine was started with the dosage of 30 mg/day and sequential add-on olanzapine (5 mg/day) yielded full symptomatic remission. She was discharged with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Soon after discharge, she discontinued medications and relapsed with hypomanic episode. After hypomanic episode lasting for four months, she developed severe depressive mood and again showed paroxysmal involuntary movements. Before admission to our hospital, she was hospitalized in a general hospital for a week because of involuntary movements and was diagnosed as “psychogenic disorder”. Finally she was admitted to our psychiatric unit.

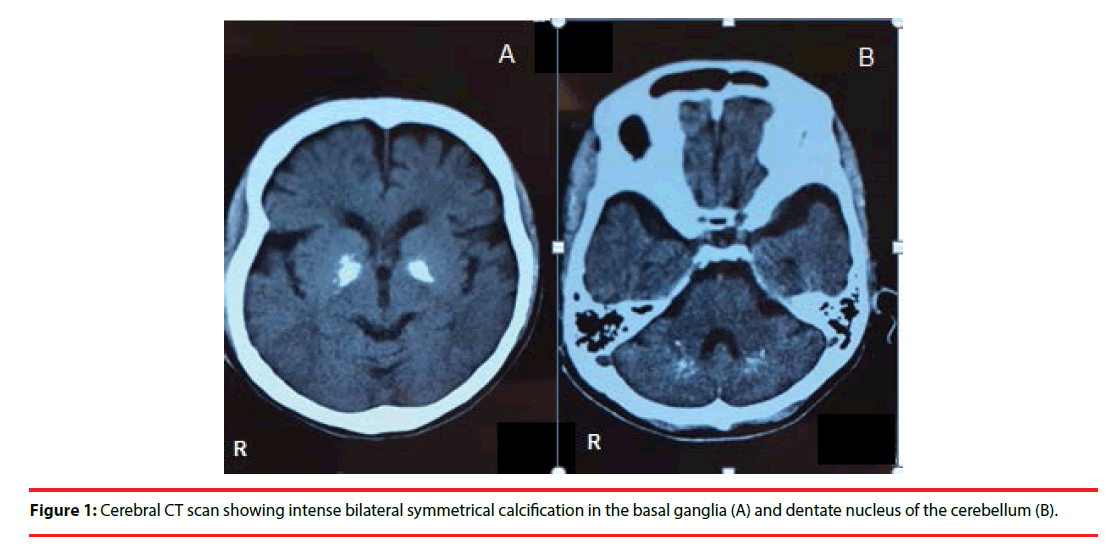

She reported bilateral dystonic abduction of the shoulders, a stiffening of her legs, inversion and dystonia of her feet, face grimaced with retraction of the mouth and tightness in her neck. The duration of the episode was 10-20 s. The episodes were occurred approximately 20– 30 times per day. During an episode, she was unable to stand and sometimes fell down. She denied experiencing any auras, tongue-biting, rhythmic twitching, loss of bowel or bladder control, headaches or sleepiness. No pain or loss of consciousness occurred during the episode. Most episodes occurred after she did sudden movements such as standing up suddenly from a seated position. She also reported “something like snake is in my body and control me”, which was like sensory hallucination. She had no other significant medical history, and there was a lack of a family history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, except for depression of her brother. General physical and neurological examinations were normal except for involuntary movements. An electroencephalogram recording for 15 min did not reveal any abnormality. Cerebral computerized tomography (CT) scanning revealed calcifications in bilateral basal ganglia and dentate nucleus of the cerebellum (Figure 1). Extensive etiological explorations, including laboratory and clinical examination, also gave normal results. Further investigations including genetic studies and magnetic resonance imaging were not performed because of lack of patient consent. Mirtazapine (15 mg/day) and olanzapine (5 mg/day) was started because this combination yielded good therapeutic response in the previous episode. Two weeks after starting this regimen, her severe depressive symptoms and involuntary movements resolved dramatically. She has been independent with her ADLs for more than five months without apparent mood changes or worsening of involuntary movements.

Discussion

This case report is the first of a bipolar patient with idiopathic BGC who showed recurrent PKD limited to depressive state, which improved dramatically with remission of bipolar depression. Reportedly, 40% of patients with BGC of various etiologies presented with psychiatric symptoms, and among patients with longstanding BGC, 31% showed unipolar mania or bipolar disorder [7]. In addition, altered activation of the basal ganglia in bipolar patients compared to healthy controls has been reported [8]. However, correlation between BD and BGC is not clear because many patients with BD do not have BGC. It is hypothesized that BGC is one of the organic factors which causes neural dysfunction associated BD, rather than the direct cause of BD.

Our case shows a challenge in the diagnosis of PKD because of its’ appearance limited to depressive state. Some previous reports regarding symptomatic PKD with comorbid BGC have shown that treatment for comorbid pseudohypoparathyroidism and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus lead to resolution of PKD [3,4]. This suggests that BGC cannot fully explain the pathophysiology of PKD and the possibility that additional conditions such as metabolic abnormalities might have a crucial role in inducing PKD. In the previous report of a 65-year-old male with BD and BGC who showed transient hyperkinetic choreiform symptoms during manic episode, mood symptoms were ameliorated with valprolate acid (1200 mg/day) and quetiapine (800 mg/day) and the involuntary movement was ameliorated with add-on tetrabenzine (75 mg/day) [9]. Although the pathogenic association between PKC and BGC has not been fully established, it is hypothesized that dysfunction of the cortico-basal ganglia circuit leads to motor symptoms [10]. Altered cortico-basal ganglia circuit connectivity, which is also thought to be associated with emotional dysregulation in affective disorders [11], might have influenced the neural connectivity related to PKC, which resulted in the appearance of transient PKD. Clinicians should consider mood disturbance as a rare, but possible causal factor of transient PKD in subjects with BD and BGC. In addition, the past reports of BD and comorbid idiopathic BGC have shown that neurological symptoms such as tremor, ataxia and dyskinesia were also observed simultaneously in depressive state [12,13]. Considering considerable evidence of the neural circuits including basal ganglia playing key roles in regulation of mood and movement as well as cognition [11], there is a possibility that patients with BGC show complex syndromes comprising not only mood disturbance but motor symptoms and cognitive disability. The relationship between BGC and mood disturbance as well as motor symptoms requires further investigation to establish the novel diagnostic and treatment approaches for BD with comorbid BGC.

As with this case, psychogenic disorder or conversion disorder, not PKD, might be first suspected if episodic involuntary movement was the most prominent symptom in depressive state. In order to avoid overlooking treatable movement disorders associated with mood disorder, careful psychiatric interventions are extremely important in cases of BD and BGC presenting with both prominent motor symptoms and apparent fluctuation of the mood state.

Conclusion

The present case suggests that clinicians should regard mood disturbance as a possible causal factor of transient PKD in subjects with BD and BGC. The optimal diagnostic and treatment approaches for BD with comorbid BGC needs further investigation considering proposed functions of the neural circuits including basal ganglia.

References

- Bruno MK, Hallett M, Gwinn-Hardy K, et al. Clinical evaluation of idiopathic paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia, new diagnostic criteria. Neurology 63(12), 2280-2287 (2004).

- Chung EJ, Cho GN, Kim SJ. A case of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia in idiopathic bilateral striopallidodentate calcinosis. Seizure 21(10), 802-804 (2012).

- Kwon YJ, Jung JM, Choi JY, et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia in pseudohypoparathyroidism, is basal ganglia calcification a necessary finding? J. Neurol. Sci 357(1-2), 302-303 (2015).

- Sanfield JA, Finkel J, Lewis S, et al. Alternating choreoathetosis associated with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and basal ganglia calcification. Diabetes. Care 9(1), 100-101 (1986).

- Kostić VS, Petrović IN. Brain Calcification and Movement Disorders. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep 17(1), 2 (2017).

- Satzer D, Bond DJ. Mania secondary to focal brain lesions, implications for understanding the functional neuroanatomy of bipolar disorder. Bipolar. Disord 18(3), 205-220 (2016).

- König P. Psychopathological alterations in cases of symmetrical basal ganglia sclerosis. Biol. Psychiatry 25(4), 459-468 (1989).

- Chen CH, Suckling J, Lennox BR, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of fMRI studies in bipolar disorder. Bipolar. Disord 13(1), 1-15 (2011).

- Roiter B, G Pigato, Perugi G. Late-Onset Mania in a Patient with Movement Disorder and Basal Ganglia Calcifications, A Challenge for Diagnosis and Treatment. Cas. Rep. Psychiatry 1393982 (2016).

- Middleton FA, Strick PL. Basal ganglia and cerebellar loops, motor and cognitive circuits. Brain. Res. Brain. Res. Rev 31(2-3), 236-250 (2000).

- Marchand WR. Cortico-basal ganglia circuitry, a review of key research and implications for functional connectivity studies of mood and anxiety disorders. Brain. Struct. Funct 215(2), 73-96 (2010).

- Casamassima F, Lattanzi L, Perlis RH, et al. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy in Fahr disease associated with bipolar psychotic disorder, a case report. J. ECT 25(3), 213-215 (2009).

- Trautner RJ, Cummings JL, Read SL, et al. Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification and organic mood disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 145(3), 350-353 (1988).