Research Article - Neuropsychiatry (2018) Volume 8, Issue 1

Metabolic Syndrome Predicts Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Elderly People: A 10-Year Cohort Study

- Corresponding Author:

- Yung-Chieh Yen

Department of Psychiatry, E-Da Hospital, 1 E-Da Rd., Yan-Chau District, Kaohsiung 824, Taiwan

Tel: +886-7-615-0011 ext. 1510

Abstract

ABSTRACT

Background: Cognitive function has been reported to predict subsequent disability and mortality in elderly people. This study aimed to explore whether metabolic syndrome (MetS) resulted in cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly people or not, accounting for depression and other risk factors during a long-term follow-up period.

Keywords

Metabolic syndrome, Depression, Cognitive impairment

Introduction

Cognitive decline is one of the major causes of disability in older people because it is often a prodromal symptom of dementia. However, identification and subsequent management of these possible risk factors may help to prevent and reduce conversion rates of cognitive decline to dementia. Numerous factors affect the risk of cognitive decline. In this context the metabolic syndromes (MetS) have always been considered risk factors for cognitive decline.

MetS is defined by the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute as a cluster of unhealthy cardiovascular disease risk factors including abdominal obesity, elevated blood pressure (BP), high levels of triglycerides (TG), low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and elevated fasting glucose (FG) levels [1]. And its prevalence is rapidly increasing with aging [2]. In the United States, the prevalence of MetS increases from approximately 7% among people in their 20s to over 40% among people over 60 years of age [3]. MetS is known to affect cognition, regardless of the mechanism, and evidence suggests that MetS, as a whole, is associated with declining cognitive function [4]. Although several studies have investigated the association between MetS and the risk of cognitive decline [5-8] in recent years, the effect of MetS on the rate of cognitive decline remains controversial [4,5]. Several cross-sectional studies have reported 2– to 7–fold increases in the risk of developing cognitive decline [9,10] among those with MetS; nevertheless, other studies have failed to discover an increased risk [11]. Therefore, the association between MetS and the risk of cognitive decline remains unclear.

In Taiwan, as life expectancy grows fast, with respect to the high prevalence rate of MetS, even a modest association with cognitive decline could have considerable implications for public health. However, the identification of the risk factors for these debilitating conditions must be a priority in order to define the best approach for early prevention. Our previous study reported that depressive symptoms and MetS are independently associated with cognitive decline among community-dwelling elderly people [12]. However; this was a cross-sectional study, which precludes the possibility of adding evidence with regard to causation. Longitudinal studies with follow-up are necessary to clarify the causal effect. Hence we aimed to build a model by this 10-year cohort to illustrate the consequent cognitive decline caused by the baseline MetS and other confounders.

Methods

▪ Study design and participants

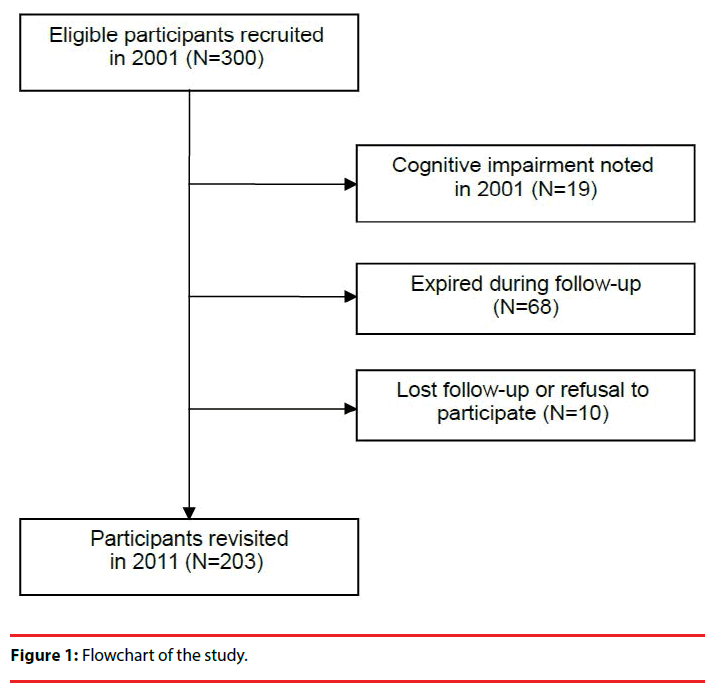

A total of 300 subjects aged 65 to 74, were randomly selected from April to June, 2001 by using the household records of 4 townships in a prefecture in Southern Taiwan, and were followed for a period of 10 years. The recruitment of the participants is demonstrated in Figure 1. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Human Research at the E-Da hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. All participants gave informed consent prior to each visit.

Participants were interviewed by trained interviewers who interviewed participants and collected data on sociodemographics (including gender, age, marital status, education level, monthly income), depressive symptoms (with the Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire [TDQ]), and general cognitive function (with the Chinese-language version of the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire [SPMSQ]). These measurements were collected at the baseline visit and 10 years after the baseline visit.

▪ Assessment of cognitive function

The SPMSQ has been used on various occasions to assess the extent of cognitive decline, and has strong sensitivity, distinctness, and reliability [13,14]. Each correct answer on the 10-item SPMSQ equals 1 point, for a maximum possible score of 10. The SPMSQ tests items such as long-term and short-term memory, directional knowledge of time and place, and other simple general knowledge questions. The questionnaire categorizes the extent of cognitive decline into 4 groups based on the level of decline: normal, mild, moderate, and severe. The test–retest reliability of the Chinese version of the SPMSQ is 0.70 [15]. The present study recorded a splithalf coefficient of alpha = 0.72. In addition, the extent of cognitive decline was determined using the following classifications: (i) for the illiterate and uneducated, a total score of 6–10 is normal, 4–5 is mildly impaired, 1–3 is moderately impaired, and 0 is severely impaired; (ii) for those with an elementary school education, a total score of 7–10 is normal, 5–6 is mildly impaired, 2–4 is moderately impaired, and 0–1 is severely impaired; and (iii) for those with a junior high school education or above, a total score of 8–10 is normal, 6–7 is mildly impaired, 3–5 is moderately impaired, and 0–2 is severely impaired. This study considered a score indicating mild decline or anything more severe than mild decline as being indicative of decline in cognitive ability, after accounting for education level. Cognitive decline in this study was defined as the lack of cognitive impairment at the first visit, but the subsequent presence of cognitive impairment at the 10-year follow-up visit.

▪ Assessment of depressive symptoms

The participants completed the TDQ, a culturally relevant questionnaire adaptable for screening for depression in community members [16]. The TDQ has a sensitivity of 0.89 and a specificity of 0.92 at a cutoff score of 19. Each answer describing depressive symptoms during the past week on the 18-item TDQ was assigned a score of 0 to 3 points, based on the symptom frequency: for a frequency of less than 1 day per week, 0; for 1 to 2 days per week, 1; for 3 to 4 days per week, 2; for 5 to 7 days per week, 3. In this study, a score of 19 was used as the cutoff point for a high likelihood of clinical depression.

▪ Diagnosis of MetS

We used a modified version of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment definition of MetS [17]. The report defined MetS as the presence of 3 or more of the following: (i) fasting plasma glucose ≥ 110 mg/dL; (ii) serum triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; (iii) serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women; (iv) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg; and (v) waist circumference > 90 cm in men and > 80 cm in women.

▪ Statistical analysis

A logistic regression was used to predict the presence of cognitive decline after 10 years based on the presence of MetS and the severity of depressive symptoms at the baseline. Sociodemographic information was adjusted in the above analyses. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

▪ Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

The study population consisted of 300 participants in the community at the baseline visit. After the initial interview, we excluded 19 participants who had cognitive impairment. At the 10-year follow-up, 10 of the participants refused follow-up, and 68 (female: 25, 11 of whom had MetS; male: 43, 10 of whom had MetS) had expired (Figure 1). Table 1 reports the characteristics of the study population at the baseline visit and the number who exhibited symptoms of cognitive decline during follow-up. Fifty-one subjects had MetS at the baseline visit. At the return visit 10 years later, 42 older adults (20.69%) with cognitive decline were observed. Cognitive decline appears more frequently in elderly females than in elderly males (p < 0.001), in people with MetS than in people without (p = 0.003), and in people with depressive symptoms than in people without (p = 0.001).

| Cognitive decline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No (N=161) | Yes (N=42) | Statistics | p |

| Sex (n) | X2(1)=17.376 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 107 | 13 | ||

| Female | 54 | 29 | ||

| Age, mean (SD) years | 68.7 (2.7) | 69.3 (3.0) | t(201)=-1.426 | 0.155 |

| Educational level (n) | X2(1)=5.074 | 0.024 | ||

| Illiterate | 61 | 24 | ||

| Literate | 100 | 18 | ||

| Marital status (n) | X2(1)=1.484 | 0.223 | ||

| Married | 129 | 30 | ||

| Other | 32 | 12 | ||

| Monthly income (n) | X2(1)=2.354 | 0.125 | ||

| Less than 1,000 USD | 111 | 34 | ||

| 1000 USD or more | 50 | 8 | ||

| Depressive state* (n) | X2(201)=10.134 | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 31 | 18 | ||

| No | 130 | 24 | ||

| Metabolic syndrome (n) | X2(201)=8.853 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 33 | 18 | ||

| No | 128 | 24 | ||

Table 1: Relationship between baseline demographic characteristic variables and cognitive decline in 10 years among participants (N = 203).

▪ The relationship between cognitive decline, MetS and depressive symptoms

Table 2 exhibits the logistic regression models from Model 1. Elderly females were associated with a 0.3–fold increase in the risk of cognitive decline (odds ratio = 0.26; 95% CI 0.12–0.58; p = 0.001). In Model 2, depressive symptoms were associated with a 0.3–fold increase in the risk of cognitive decline (odds ratio = 2.96, 95% CI 1.40–6.22, p = 0.004) and MetS was associated with a 0.3–fold increase in the risk of cognitive decline (odds ratio = 2.73; 95% CI 1.30–5.72; p = 0.008). In Model 3, after adjusting for age, gender, education level, marital status, and income, we observed that the presence of MetS at the baseline visit was associated with a 2.7– fold increase in the risk of cognitive decline (odds ratio = 2.66; 95% CI 1.21–5.85; p = 0.01), and depressive symptoms were associated with a 2.4–fold increase in the risk of cognitive decline (odds ratio = 2.37; 95% CI 1.03–5.46; p = 0.04) in community-dwelling elderly people. Elderly males had a lower probability of cognitive decline than that of elderly females (odds ratio = 0.29; 95% CI 0.12–0.68; p = 0.004).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Male vs. Female | 0.261 (0.116 0.583) |

0.001 | 0.294 (0.127 0.681) |

0.004 | ||

| Age (years) | 1.061 (0.938 1.201) |

0.346 | 1.088 (0.954 1.239) |

0.208 | ||

| Literate vs. Illiterate | 0.781 (0.361 1.693) |

0.532 | 0.989 (0.422 2.316) |

0.979 | ||

| Married vs. Non-married | 0.859 (0.373 1.981) |

0.722 | 0.921 (0.382 2.217) |

0.854 | ||

| Monthly income>1000USD vs. else | 0.565 (0.234 1.365) |

0.205 | 0.597 (0.240 1.483) |

0.266 | ||

| Depressive vs. Non-depressive state | 2.960 (1.408 6.222) |

0.004 | 2.376 (1.034 5.461) |

0.041 | ||

| Metabolic syndrome vs. else | 2.727 (1.300 5.719) |

0.008 | 2.666 (1.214 5.856) |

0.015 | ||

Table 2: Logistic regression models predicting cognitive decline in 10 years (N = 203).

Discussion

When using a community-based prospective cohort of individuals with intact cognition, participants with MetS display an increased risk of cognitive decline after 10 years follow-up. These associations remained after adjustment for demographic variables, education level, income, and marital status. The association between MetS and cognitive decline is more apparent in women than in men. Based on our research, the present study is the first to investigate the association among MetS, depression, and cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly people.

These results are in general agreement with prior longitudinal studies that have followed individuals for shorter periods (2 to 5 years). Those studies have reported that in elderly MetS is associated with an increased risk of clinically defined cognitive decline [8,13] and cognitive decline [4,8,18], with global function, memory, and executive abilities particularly affected. Yaffe and colleagues discovered that in elderly Latinos, those with MetS have greater cognitive decline than do those without, as measured using the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination and the Delayed Word-List Recall [6]. A smaller study, involving 101 older women, reported that MetS is associated with an increased risk of global cognitive decline and memory decline after 12 years. This study measured global cognitive function by using the Mini-Mental State Examination and memory by using the Word Recall Test with 3 words lists [19]. In one longitudinal study involving 993 elderly persons, MetS was discovered to be a risk factor for accelerated executive function (Trails B) and long-term verbal memory, particularly among women [22]. The study focused on measuring the association between MetS and the trajectories of cognitive change. Our study focused on evaluating the association between MetS and the risk of cognitive decline. Overall, these studies have found a significant association between MetS and cognitive function. This result could be explained with a statistical analysis of a similar population. Additionally, Vanhanen and colleagues reported no significant association between MetS and the risk of Alzheimer disease among men but reported an association among women [10]. Gender differences in the association between cognitive function and MetS have not been widely explored. MetS is a stronger predictor of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular-disease-related mortality in women than in men [21]. It is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in women, but not in men [22]. Thus, these results support that women with MetS exhibit an increased incidence of cognitive decline compared with men with MetS. Another study that focused on the oldest adults (≥ 85 years) failed to reveal a link between MetS and cognitive decline, but this result might be related to survival bias [5].

The mechanisms underlying an association between MetS and cognitive decline are not completely understood, but there are several plausible pathways. Those studies have found that hyperglycemia is the main contributor to the association between MetS and cognition in elderly. Hyperglycemia, a marker for insulin resistance and the main feature of MetS, may have direct negative effects on cognition, whereas such direct effects have not been discovered for the other components [23]. Another probable mechanism is the effect of the elevated inflammation often seen in patients with MetS [7,23] Markers of inflammation have been associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline and developing dementia [7]. Inflammation may also be viewed as part of MetS. Further study is necessary to understand the role of inflammation in MetS and cognitive decline.

Our study has numerous strengths, including the use of a population-based cohort with long follow-up, the collection and standardization of MetS data, and inclusion of both genders. Finally, we were able to adjust for major confounders, such as age, education level, depression state, marital status, and monthly income.

However, there are limitations in our study. First, depressive symptoms are associated with a 2.4–fold increase in the risk of cognitive decline. This may explain why we found an association between depressive symptoms and cognitive decline. An alternative explanation is that depressive symptoms may overlap with the symptoms of cognitive deterioration. Additionally, we must establish a standardized measure to assess depressive symptoms. However, depressive symptoms are associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline. Although there is evidence that depression predisposes cognitive decline, the causal relationship between them may be considerably more complex [24,25]. Second, 68 older adults (female: 25, male: 43) died before the follow-up. Survivor bias, a potential limitation in studies involving aging populations, could have led to an underestimation of the true association between MetS and cognitive function, but it is unlikely to be solely responsible for the association. Although numerous covariates were accounted for, incomplete control of confounders and the effect of unknown confounders may still be present. In this study, we found that patients with MetS have an increased risk of cognitive decline, especially elderly women. Future research should assess whether identifying cognitive decline among patients with MetS yields outcomes that are more favorable than those achieved by controlling clinical factors more aggressively.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (NSC 89-2413-H-182- 005, NSC 90-2413-H-006-015, NSC 91-2413- H-006-006 and NSC 97-2314-B-650-003-MY3) and E-Da Hospital (EDAHP101006, EDAHP 103006, EDAHP106021), Taiwan.

This funding is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicting of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American heart association/National heart, Lung, and blood Institute Scientific statement. Circulation 112(17), 2735-2752 (2005).

- De Luis DA, Lopez Mongil R, Gonzalez Sagrado M, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome with International Diabetes Federation Criteria and ATP III Program in patients 65 years of age or older. J Nutr. Health. Aging 14(5), 400-404 (2010).

- Lau DC, Yan H, Dhillon B. Metabolic syndrome: a marker of patients at high cardiovascular risk. Can. J. Cardiol 22 (Suppl B), 85B-90B (2006).

- Yaffe K. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline. Curr. Alzheimer. Res 4(2), 123–126 (2007).

- van den Berg E, Biessels GJ, de Craen AJ, et al. The metabolic syndrome is associated with decelerated cognitive decline in the oldest old. Neurology 69(10), 979-985 (2007).

- Yaffe K, Haan MN, Blackwell TL, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in elderly Latinos: findings from the Sacramento Area Latino Study of Aging study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 55(5), 758-762 (2007).

- Yaffe K, Kanaya AM, Lindquist K, et al. The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline. JAMA 292(18), 2237-2242(2004).

- Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Logroscino G, et al. Current epidemiological approaches to the metabolic-cognitive syndrome. J. Alzheimers. Dis 30: S31-75 (2012).

- Razay G, Vreugdenhil A, Wilcock G. The metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. Arch. Neurol 64(1), 93-96 (2007).

- Vanhanen M, Koivisto K, Moilanen L, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with Alzheimer disease, a population-based study. Neurology 67(5), 843-847 (2006).

- Muller M, Tang MX, Schupf N, et al. Metabolic syndrome and dementia risk in a multiethnic elderly cohort. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord 24(3),185–192 (2007).

- Chang TT, Lung FW,·Yen YC. Depressive symptoms, cognitive decline, and metabolic syndrome in community-dwelling elderly in Southern Taiwan. Psychogeriatrics 15 (2015).

- Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J. Gerontol 36(4), 428-434 (1981).

- Pfeiffer E. A Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 23(10), 433-441 (1975).

- Chi I, Boey KW. Validation of Measuring Instruments of Mental Health Status of the Elderly in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Department of Social Work and Administration, University of Hong Kong; (1992).

- Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger, M, et al. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am. J. Epidemiol 106(3), 203-214 (1977).

- Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285(19), 2486-2497 (2001).

- Raffaitin C, Feart C, Le Goff M,et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in French elders: the Three-City Study. Neurology 76(6), 518-525 (2001).

- Komulainen P, Lakka TA, Kivipelto M, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive function: a population-based follow-up study in elderly women. Dement. Geriat. Cogn. Disord 23(1), 29-34 (2007).

- McEvoy LK, Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Metabolic syndrome and 16-year cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults. Ann. Epidemiol 22(5), 310-317 (2012).

- Pischon T, Hu FB, Rexrode KM, et al. Inflammation, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of coronary heart disease in women and men. Atherosclerosis 197(1), 392-399 (2008).

- Boden-Albala B, Sacco RL, Lee HS, et al. Metabolic syndrome and ischemic stroke risk: Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke 39(1), 30-35 (2008).

- Dik MG, Jonker C, Comijs HC, et al. Contribution of metabolic syndrome components to cognition in older individuals. Diabetes. Care 30(10), 2655-2660 (2007).

- Wilson RS, Mendes De Leon CF, Bennett DA, et al. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in a community population of older persons. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 75(1), 126-129 (2004).

- Yaffe K, Weston AL, Blackwell T, et al. T The metabolic syndrome and development of cognitive decline among older women. Arch. Neurol 66(3), 324-328 (2009).